We can usefully think of urban form as the “shape of habitable space”. 1 This allows us to move beyond representational or semantic notions of society in space to talk about the particular material qualities that enable action, or constrain it, in particular ways. This does not mean that architecture dictates or predicts behaviour. Material and network properties of urban space create ranges of possibilities, which will have different relationships to norms, legality, transgression, and so on, in different historical and cultural settings. The important thing is that space, in its planned or organic organisation through building, is an active agent in “generating and restricting a field of encounter”. 2 This is what Bill Hillier calls “spatial culture”: 3 the distinctive way a society orders space so as to produce principles, or possibilities, for the ordering of social relations, not the control of individual relationships or acts. There is much work in the field of spatial cultures, or urban morphology, that describes how the shape of space is tied up with its social, economic, cultural possibilities. There is a much smaller, but growing, field of work that describes similar possibilities in relation to urban sound.

Acoustics are material properties of space, governed by things like the texture and geometry of surfaces, and the volumes those surfaces contain. Acoustics do not describe how spaces sound, though: they describe how space and sound interact. For there to be sound, there must be some form of action, and for there to be action, time must pass. Acoustics, then, are only meaningful in an interplay of action and space over time. Visual aesthetics of space can be frozen in images, and studied semantically in a network of static symbols that supposedly represent society or culture in various ways. Acoustics are arguably closer to a lived experience of culture, constantly emerging from embodied usage in relation to an active environment that shapes possibilities.

This is not to say that hearing now needs to be privileged above the visual, but that enriching the ability of built environment practices to understand sound better is very valuable. There are two main reasons in my mind that this is very important for urbanism now. Firstly, because the acoustic properties of space are not representational but immediate. For example, the turbine hall of a power station might have the same acoustic as a cathedral, but this does not mean it sonically represents Christianity. Instead of a literal reference, it actually creates the same set of sonic possibilities through particular reverberation times and so on, and this can only be experienced as a listening subject in the space itself. The display of a crucifix in this space might symbolically imbue it with religious connotations but it doesn’t change its material possibilities. This symbolic communication works equally in an image as it does in the flesh. This leads to the second reason, which is the visual bias in urbanism that is a product of the tools of its craft, as described by Richard Sennett in The Craftsman. 4 It is not necessarily inevitable that urban design is sketched and tested out on screens rather than through embodied and situated kinds of practice, but the way it has developed historically as a technical professional discipline means this is the case. The Craftsman makes an argument for non-discursive kinds of knowledge that are developed through habitual relationships, built up between bodies and bodies, and bodies and space. To understand the mobilising possibilities of urban acoustics requires being present in space, and being attuned to properties that cannot be contained in a two-dimensional static plan. It requires a sensorial relationship between the body of the designer and the object of their craft.

If acoustics are a set of static material possibilities contained in urban form, sound is the dynamic material that mobilises those possibilities. What, though, is sound? It seems to me, from a human perspective, to be able to be organised largely into broad forms such as speech, music, and noise. In any given context, I would have thought, we could fairly well agree on which of those labels any source of sound belongs to. However, as Brandon LaBelle points out, that categorisation is geographically contextual. As a simple example, the muffled thump of a bass drum coming from an apartment above is very much unwanted noise from where I am sitting, but it forms part of the organised sound of music within its own space. In Acoustic Territories, 5 LaBelle traces out an ethics of the different ways sound is produced and received across spaces such as the street, the prison, and the home, and through in cultural contexts through history. Jacques Attali takes a more universalist approach, describing noise as the primordial threat of disorder and destruction and music as the taming of noise into ritualised forms of music as the creation of society, with power lying in the hands of those that have the ability to shape our understanding of the form that ritual should take. 6 LaBelle sees power more as the ability to silence, often using written law to impose a sonic order. He describes protest as sound-making that breaks that sonic order, often using the city as an “acoustical partner”, transgressing the expected ways that its acoustic possibilities are mobilised. He says: “The ideological fact of racial tensions finds articulation in the printed word, as with newspapers and legal documents. Yet it poignantly presses in on real bodies through acts of vocality, forceful argument, and hate speech”. 7 So the visual, including text, represents, while immediate sound acts upon us physically. In any case, what is determined to be noise, and how that noise is dealt with, can only be seen highly political.

Thinking of the example of the protest, an analysis of sound-making is a way to describe different ways of being in public. The same gathering of people could be transformed from a crowd to a protest simply through a change in vocality from a hum of background chatter to a unified chant. Or in turn an audience, a congregation, and so on. If we add in acoustics, that might amplify, echo, or dampen those voices, we start to see how different conditions of publicness are made possible through a set of material relations between sound-making and material form. Taking the notion of theatrum mundi 8 literally, the street becomes a stage when the crowd makes specific, even if unconscious, use of the acoustic properties of space to amplify its presence, in the way auditorium design helps musicians project sound to an audience. Rather than talk about this in the abstract, though, I would like to turn to back to Paris’ périphérique.

To recap, my argument is that architectural space is a set of material possibilities; acoustics are the relationship of sound to space; the production and reception of sound is political. So can the social conditions of space be described sonically? I want to look now at three spaces along the Périphérique in north-eastern Paris: Portes de Montmarte, Porte de la Chappelle, and Porte des Lilas. I won’t talk about the history and spatial politics of the Périphérique itself, as I’m sure you all know more about that than I do. But it is important to remember these portes are the subject of an attempted “reconquête urbaine”, 9 with funds from the city’s participatory budget for small interventions to transform them into places – de portes en places – presumably suggesting that in their current form they are kinds of “non-places”.

I would like to say that the Périphérique is, as well as a barrier to movement and visibility between Paris and its suburbs, an acoustic barrier, though its architectures create spaces with particular acoustics that seem to make possible different kinds of public life, and I would like to describe the way I have observed that process at each of these spaces.

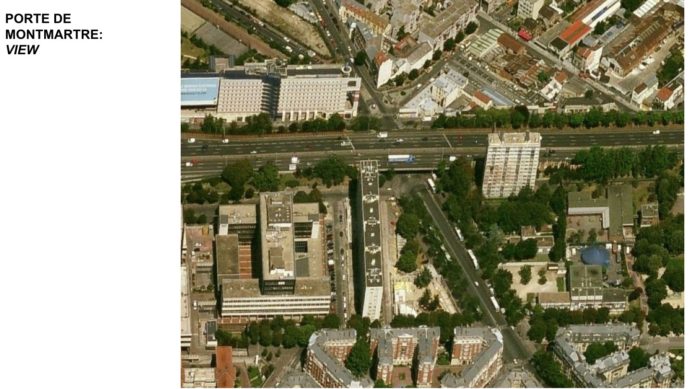

Porte de Montmarte

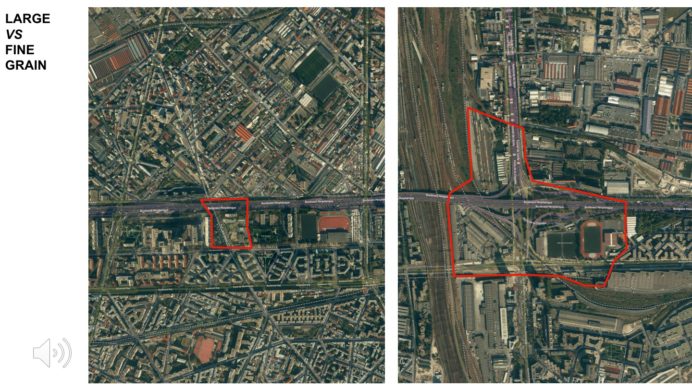

At the junction of boulevard de Montmarte the Périphérique runs overhead on a simple viaduct with little interruption to the fabric of the built environment on either side, which butts against it in a dense grid (slide 1). You could say, then, that there is a continuity of habitable space between intramuros and extramuros Paris here. Though the Périphérique remains a visual and acoustic barrier, it does not constrain movement on foot (slide 2). So the space underneath it is highly accessible, creating a simple canopy over a road that is otherwise quite typical in size and form for a Parisian boulevard (slide 3). In a scale of publicness, highly accessible space can also be thought of as highly public, tending to create the conditions for greater volumes of movement and presence. The Porte de Montmarte was for years the site of an informal biffin (street flea market), that more recently has been formalised and approved by the city. 10 Without the usual market infrastructure of stalls that separate customer and vendor, the biffin takes the form of an intense crowd of bodies jostling for room in the tight pavement spaces contained under the viaduct(slide 4). As Canetti observed, the crowd is a vehicle for identity-forming, but could easily tip into destruction. Though the viaduct provides shelter from the weather, I wonder whether this is the only reason the biffin emerged there. On the three occasions I have visited it, the weather has been fine, but still it is concentrated underneath the Périphérique.

As well as shelter, another material quality of this space is a reverberant acoustic. It is well contained, and has hard surfaces that and angular recesses propagate sound through a series of reflections. As a space of intense commerce and transaction, there is a constant hum of voices negotiating and communicating with one another, punctuated by traders who call their wares. The canopy has two effects on these voices compared to open air space: it reflects them back to their source; and it extends them through reverb, meaning they lingers longer in the space. This intense gathering plus the particular reverberance of the space leads to the dominance of human voices over traffic noise, and the combining of these voices into one sonic whole. It is a sociological question to ask: when does a crowd of bodies becomes a public with some form of cohesion? What happens to the crowd when it is reflected back at itself, and when its sounds bloom and mingle together? Its presence seems to be amplified, a self-assurance, and gain an intensity that a similar-sized gathering in open-air would not possess. It seems relevant here that this crowd is highly policed, with a significant number of officers observing it from horseback. It is also worth mentioning that since I first visited the site, a design intervention has added a visual décor to the space that itself uses mirrors to reflect the image of the crowd back to itself. I haven’t quite yet figured out what this means, but it strikes me that this aesthetic dressing of the space adds a symbolic layer but does little to change its actual possibilities.

Porte de la Chappelle

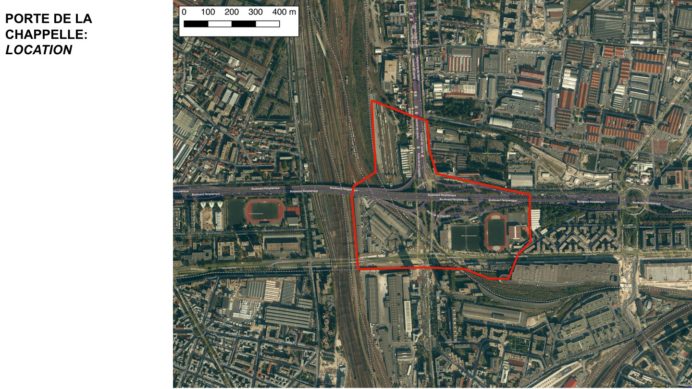

At the junction with Boulevard de la Chappelle the Périphérique opens up into a tangle of slip roads, interwoven with raised and sunken train lines. Whereas Porte de Montmartre is really just a node at the meeting point of two lines, just the junction of Porte de la Chappelle occupies an entire territory of its own (slide 6). Unlike Montmartre, which is a small interruption in the fabric of inhabited space, Chappelle creates an entire infrastructural zone occupied by non-residential space such as warehouses, sports pitches, train sidings (slide 7).

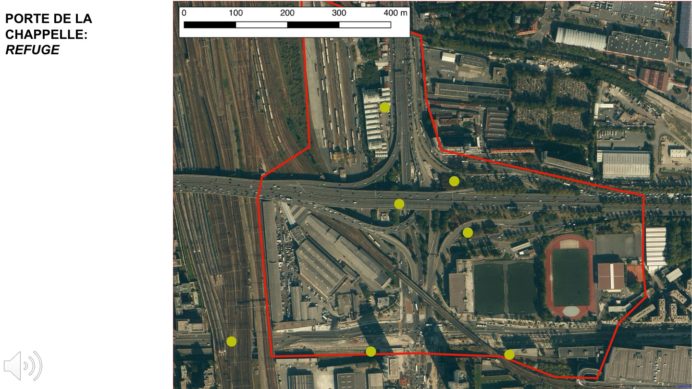

As well as having two-dimensional extension, it consists of several vertical levels and infrastructure for at least five modes of transport. It creates a significant break in the shape of inhabitable space, again from the bourgeois pedestrian perspective. From what I could tell, it was at least ten minutes walk from the metro and shops inside to the first ‘inhabitable’ space outside. Compare the junction at Porte de la Chappelle at scale with the underpass at Porte de Montmartre (slide 15) to see how different the kinds of space we are dealing with.

This intermuros space – neither within or without but between the walls – is devoid of bodily noise, dominated instead by the infrastructural sounds of industry and transport (slide 9). Furthermore, because of the fragmentation of the Périphérique here into separate strands, plus the lack of recesses in its canopy, and the greater height of the viaducts, it does not create the same concentrated, reverberant space (slide 10). Within this thick barrier are many indeterminate green spaces. Extremely inaccessible, they do not have transactional or public value in the way the intense commercial space of Porte de Montmartre does. Due to their inaccessibility, they can instead be claimed for dwelling: a private, vulnerable activity. As well as the large migrant encampments around Porte de la Chappelle, which last week (at the time of writing) were cleared again, there are many smaller sites of temporary living. Each occupied by a handful of people, we might call these communities rather than publics: inward-looking, private, and functional, rather than performative (slide 11). I want to suggest though that it is inaudibility as well as inaccessibility that creates the conditions for this dwelling to be possible. When people can’t use walls to prevent themselves from being heard outside their intimate domain, does infrastructural noise create a mask that offers privacy? Given my sense that Porte de la Chappelle was offering a sanctity of invisibility and inaudibility I didn’t want to jeopardise this by photographing or recording these communities closely. A quick mapping showed several distributed within the various spaces of the junction itself, not to mention the large formal and informal migrant camps on the disused petite ceinture rail line just within the Périphérique (slide 13).

Comparison

Comparing these two spaces offers two different notions of what noise is and can do at the Périphérique. The crowd at Porte de Montmartre performs its presence with a cacophony of voices which are extended and amplified by the infrastructural acoustic. Its heightened presence seems to become threatening enough to a social order that it must be heavily policed. In terms proposed by Richard Sennett, it is a border that draws activity to it and creates heightened interaction. The community finds shelter within the indeterminate territory of Porte de la Chappelle. It hides its presence under a blanket of vehicular white noise, which is known for its ability to suppress other sounds, carving out a space of intimacy between small groups of people living together. Here in Richard’s terms, the Périphérique is a boundary that repels activity and strongly divides, but in doing so it becomes a refuge.

A sonic urbanism?

Briefly, to finish, I want to return to the question of whether sound is a way of re-crafting urban practice, I want to describe two major design interventions at the Périphérique in these terms.

Firstly, the Porte des Lilas (slide 16), where a cover has been placed over the Périphérique to create a landscaped green park (slide 17). This kind of approach comes from an ethos of urban “liveability”, which itself is a bourgeois notion of the city as a mode of living that is rightly safe and pleasurable. Definitely this intervention creates a new set of spatial possibilities, while presumably erasing an old one. So I don’t want to say that it is purely symbolic. But it is also, evidently, an attempt to silence the noise of the Périphérique. Whilst traffic noise is normatively thought of us unwanted in the context of residential space, I would argue that portraying it as such is a political act based on an ideological notion of who and what the city is for. Silencing is the enactment of power, and the creation of a tabula rasa that erases pre-existing acoustic possibilities, to ease the expansion of the urban bourgeois into spaces that were previously perceived as sonically inhospitable.

Finally, the new Philharmonie de Paris, which goes beyond the assertion that quiet is possible at the Périphérique, to say that it can also be the site for the most rarefied forms of organised sound, which are presented in highly ritualised gatherings that reproduce bourgeois social identity. In Attali’s terms, music is the assertion that society is possible, and the Philharmonie strikes me as a strong desire to show that a dominant sonic culture can even be possible at the fringe, with all its untameable and threatening noise.

Originally given as a presentation at the seminar From noise to music on 12th May 2017 at Collège d’études mondiales, FMSH Paris. It is based on research undertaken on a postdoctoral fellowship provided from 2016-2017 by the Collège as part of the Global Cities chair.

- Penn, Alan. "The shape of habitable space." UCL, 2003.

- IBID

- Hillier, Bill. "The architecture of the urban object." Ekistics (1989): 5-21.

- Sennett, Richard. The craftsman. Yale University Press, 2008.

- LaBelle, Brandon. Acoustic territories: Sound culture and everyday life. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2010.

- Attali, Jacques. Noise: The political economy of music. Vol. 16. Manchester University Press, 1985.

- LaBelle, Brandon. Acoustic territories: Sound culture and everyday life. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2010. p 112.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatrum_Mundi

- https://budgetparticipatif.paris.fr/bp/jsp/site/Portal.jsp?document_id=2208&portlet_id=158

- http://www.leparisien.fr/paris-75018/paris-la-porte-de-montmartre-en-quete-de-rehabilitation-21-03-2017-6783336.php