Scores and actions

A score is a guide for action, with varying degrees of prescriptiveness. A score is knowledge encoded in media – a guide for making music conceived by a composer in one context, read by a performer, and used by them as a prompt to do something that makes sense in their own context. A score can be a way of coordinating a group of people, strangers even, around a shared set of actions. People that may not share ideological, linguistic, aesthetic codes move together, with the score as a map. In fact, maps can also be like scores, in that they encode knowledge about the shape of the world, suggest how to navigate, but ultimately place agency with they who read the map. Scores are sticky – rather than allowing us easily to slip past one another they provide a texture, a friction that generates a common rhythm. Just like maps provide common routes and landmarks that pattern flows of people in the city. Scores can also be used as tools of control though, even violence, when they are used to dictate total submission to a highly structured whole, and this capacity has not gone unnoticed by dictatorial regimes that use epically-scaled choreographies to demonstrate and reinforce the discipline of their subjects’ bodies. Others are merely a suggestion, hold back even from suggesting any particular action and simply present themselves as artefacts after which a performance may or may not come. This too is a kind of dictation – it enforces total independence of the musician or dancer, does not offer to share the labour of making a performance through the laying of an infrastructure on which the moment of performance is built. A score is a way of communicating an idea about how things could sound, or move, but also a way of recording how things have already sounded and moved.

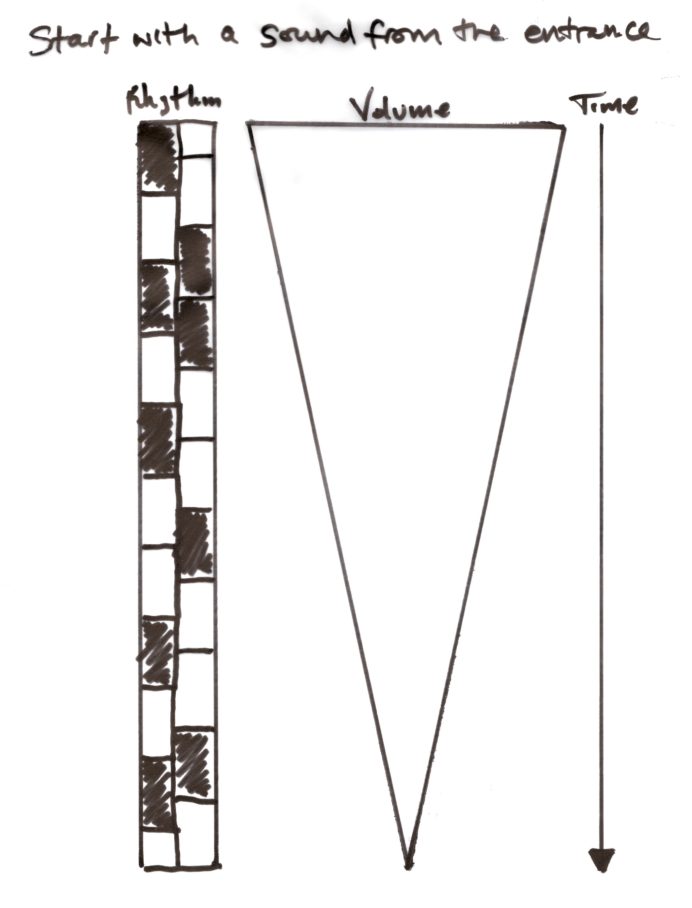

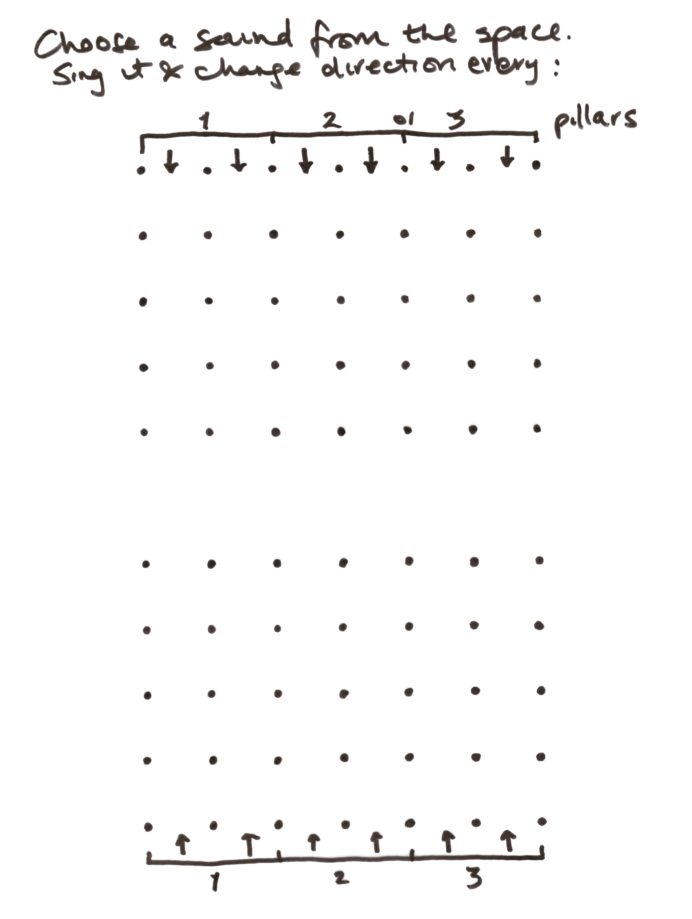

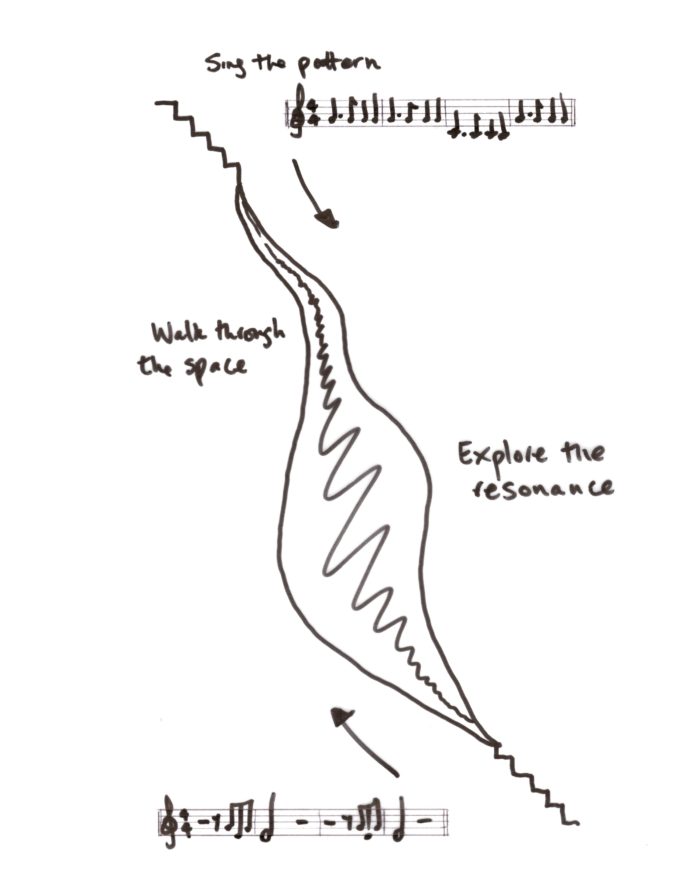

Here we offer scores that come both before and after a performance. Building on Azpilicueta’s previous work, sonic conditions generated by mechanical and spatial phenomena echo through the body of the artists and are transformed in the process. These echoes become a non-linguistic way of communication about and through shared sensory experience – finding in languages heard as much as in noise a set of patterns and rhythms. Scores allow us to pass on this mode of communication: to a performer, into an object, and back to you. These works are artefacts generated by translating acoustic and spatial conditions in the urban environment via the bodies of the artists, into scores, into performing bodies, and from those bodies into sculptural form. Every score is always only a moment on a chain of events framed by architecture: space – composer – performance – score – musician – performance – space. Similarly with these works – they are not just final things but part of a network of moments of creation: listening to the city, translating its sounds and spatial forms into bodily actions, performing them back to the spaces they are derived from, encoding and passing on these actions to others, decoding them, recording them, re-encoding them as three-dimensional scores, and presenting them here as a set of possible actions within those spaces. They are proposals rather than facts, knowing-to rather than knowing-that, from the narrowness of being to the breadth of doing and the new situations it produces which take us out of a current state and into new rhythms. The recordings are one set of versions in the same way that no performance of Verdi can be definitive.

Acoustics and voices

Before electronic amplification and mediation were possible, opera was a way of making human subjectivity a public matter – not only through narrative but through the affective qualities of the voice itself. We do not need even to understand the language carried by the operatic voice: we can physically feel pain, death, and ecstasy through its penetration of the spectating body. One person’s private tragedy or joy becomes a shared concern, not through being told (though that it is of concern) but through a visceral response, what Jacques Rancière calls a “community of the senses” or sensus communis. Meanwhile, debates are raging in Europe about the right for human subjectivity to be hidden in public. Moves to ban facial coverings are based on the notion that to be considered a legitimate member of the public we must expose our bodies. But is it not with our voices that we truly participate in the public sphere? The voice represents the ability to communicate, to vote, to protest, to speak out, and to have agency over what is made public. Instead of forced corporeal exposure masquerading as a democratic ideal we should be seeking new ways to amplify the voice, building a public realm perhaps around hearing one another.

What is the importance of the voice, hearing one another without words? In this work we have chosen not to burden the voice with language so that it demands full attention, and rather used it to focus attention outwards onto the way it responds to and activates its environment. Words can often act to highlight difference whereas the pure materiality of the voice is held deeply in common. It is the interior of the body made public, a flow of air from inside to outside via a fleshy resonating box. It makes material vibrate, it acts physically upon other bodies around it in ways they cannot control, bringing them into a shared pattern, like the score itself. But the voice does not act alone in doing this, it is aided by acoustics which are properties of architectures. Acoustics are technologies for the transformation of the voice. In the opera house, they are designed consciously to expand the human voice beyond its natural capacity but they are also built into the everyday environment, often accidentally. They are somewhat like scores, in that they are possibilities for certain kinds of sounds, that only become audible through action. Sound is always generated through the friction between action and container, it is the by-product of the flow of bodies through these spaces and it sits in different registers – psychological, material, acoustic friction. The way, for example, shoes agitate the surface of the Maastunnel, but also how this agitation is amplified as its ripples meet the curved tiled surfaces; but also the way the pillars of the Mevlanaplein rail bridge punctuate our awareness as we walk through the space; or that the expanding and contracting resonances of Wilhelminaplein station bring us to attention. All these things have the potential to act as a kind of drag effect to slow down or ground awareness as it becomes attached to surroundings.

These scores, then, are an invitation to find expanded sonic capacities beyond the opera house and out in the city. We invited the public to join us on 25 May at Mevlanaplein to join a collective realisation of the score for this site, and to take what they learn on to the other spaces we have proposed as well as settings all over the city that amplify their new-found voices.

Written for Scores for Rotterdam, a project by Mercedes Azpilicueta and John Bingham-Hall for the exhibition Post-Opera at TENT Rotterdam, curated by Kris Dittel and Jelena Novak. The project is exhibited as three sculptures accompanied by sound works, and included a public activation at Mevlanaplein in Rotterdam on 25 May 2019.